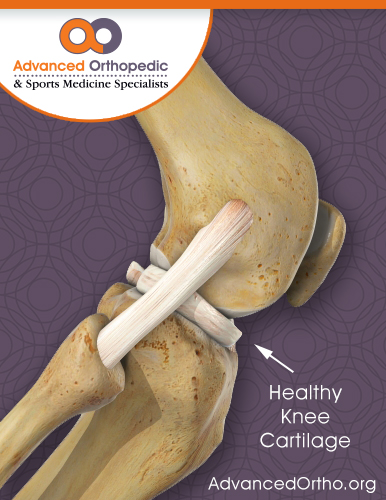

You have probably heard a friend or family member complain of pain from the friction of a “bone-on-bone” joint problem. But what’s behind this often-agonizing pain and what’s missing? In a word: cartilage.

What is cartilage?

Cartilage plays a critical role as a cushion and smooth surface that helps our joints glide as we move. But if you have cartilage damage or deterioration, that gliding is replaced with friction, and you know all too well how excruciating the pain can be.

Because blood does not flow to and from our cartilage, it heals very slowly, and typically requires surgery to repair. There is a silver lining to all this bad news: modern techniques make repair – and even new tissue growth – possible, and these procedures help protect joints against future problems like arthritis.

How do I know if I have cartilage damage?

The most common place we see cartilage damage is in the knee joint. Because cartilage is not bone, damage and deterioration cannot be seen on x-rays. But if you are experiencing significant joint pain with movement, it’s best to see a specialist. “Cartilage damage often can be associated with other joint injuries,” says Dr. Wayne Gersoff, who specializes in articular cartilage restoration. “But in other cases, we identify damage by using an MRI scan and sometimes arthroscopy.”

What are my treatment options?

According to the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, the best candidates for cartilage restoration of the knee are typically young adults with a focal injury. Older patients, or those with multiple problems, including degenerative joint disease, are less likely to benefit from surgery.

If you are a good candidate for knee surgery, one of six major procedures might be recommended. These solutions have evolved to become minimally invasive in most cases, and many involve processes that use the patient’s own cartilage or healing capability to repair the injured joint.

- Microfracture helps to preserve and restore function by allowing the patient’s own body to repair the damage. Small holes are drilled on the surface of the knee where the cartilage is defective. Resulting blood clots prompt the formation of a cartilage-like scar and regenerate repair tissue.

- Chondral transfer involves a transfer of cartilage from a non-weight-bearing location in the joint to a damaged, weightbearing area. By replacing cartilage in defective, weight-bearing areas, patients will have healthy cartilage where they need it the most.

- Autologous chondrocyte implantation removing cartilage cells from a non-weight-bearing area of the knee. The cells are sent to a laboratory where they can be cultured to grow more cartilage cells. The new cells then are transplanted back into the patient to replace large cartilage surface defects in the knee. These cells grow repair tissue that is quite similar to original cartilage.

- Osteochondral allograft surgery uses bone and cartilage from a deceased donor to replace deficient cartilage in patients’ knees.

- Meniscal allograft: also uses meniscus from a deceased donor to replace meniscal cartilage deficiencies.

- Osteotomy is a complementary procedure that involves cutting the bone to change its alignment to improve the outcomes of cartilage restoration.

Any of these procedures may help replace damaged cartilage, decrease pain and delay arthritis in the knee. If you think you have cartilage damage, don’t suffer. Make an appointment with a specialist for proper diagnosis, and to prevent or slow future problems.

For more information on cartilage damage and repair, visit this page on cartilage.org or the education page on sportsmed.org